Migration and Climate

Policy researcher and strategist specializing in migration and mobility

Scott Drinkall is a policy researcher and strategist focused on migration, climate change, and community resilience.

Consultant, Nexight Group - Helping clients cut through complexity—translating data and policy challenges into clear insights and strategies that drive real-world impact.

Doctoral Student, George Mason University - I work with communities experiencing the effects of climate change, translating their experiences into evidence-based insights to inform smarter policy solutions. This entails fieldwork in Hawai’i and the Federated States of Micronesia (January 2023 and December 2023).

I have advised leaders in Hawai‘i, conducted fieldwork across the Pacific and Asia, and supported projects at the United Nations. This work brings clarity to complex policy challenges—whether shaping regulatory frameworks, advancing public health, or exploring how climate change reshapes mobility.

As a former Visiting Researcher with the Environmental Law Institute, I supported the development and application of a “Migration with Dignity” legal and policy framework. As part of this global effort, I have led two research projects in Oregon (2018 and 2021) on the migration experience of Pacific Islanders.

About

Upcoming Research

Navigating Home: Return Migration Intentions Among Pacific Islanders

Federated States of Micronesia (remote)

Return Migration in Micronesia: An Inquiry into Reintegration

Salem, OR or Springdale, AR

Pacific Islanders face a dual reality: rising seas and intensifying storms threaten their homelands, while opportunities and stability in the United States pull them away. Under the Compacts of Free Association (COFA), citizens of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau can move freely between both worlds—making their return migration decisions especially revealing. This study uses surveys and interviews to explore why some Islanders consider going back, what holds them in the U.S., and how climate change and identity shape those choices. By centering the voices of a highly mobile yet underrepresented community, the research offers fresh insights for climate mobility scholarship and delivers practical guidance for policymakers and organizations supporting Pacific Islanders at home and abroad.

Return migration remains an underexamined aspect of global mobility, especially within Small Island Developing States (SIDS). In Micronesia, most scholarship focuses on outward migration and diaspora communities, leaving returnees’ experiences largely unexplored. This study will investigate how Chuukese migrants navigate identity, belonging, and reintegration after returning from abroad. Drawing on semi-structured interviews with returnees, the research examines three dimensions: identity negotiation, decision-making factors, and reintegration challenges and supports. An interpretivist, grounded theory approach allows themes to emerge directly from participants’ narratives, while reflexivity ensures attention to power dynamics and positionality. By centering returnees’ voices, the study advances understanding of migration as a circular and identity-driven process, with implications for policy, development, and broader migration theory.

Global Research, Local Partnerships

I’ve worked across the Pacific, East Africa, and Asia—partnering with communities, governments, and international organizations to address pressing challenges in migration, climate change, and public health.

Publications (selected)

International Migration Review

The Effect of Slow-onset Climate Change on Migration Decisions

2025

PS: Political Science & Politics

Ebb and Flow: The Prospects and Constraints and Climate Migrants

2024

Journal of Disaster Research

Migration in the Midst of a Pandemic: A Case Study of Pacific Islanders in Oregon

Journal of Disaster Research

2019

2022

Conferences/Presentations

George Mason University Panel

February 10, 2025

The Schar School of Policy and Government organized a series of doctoral student workshops, including one on presenting and publishing papers.

As one of GMU’s doctoral students who has published in well-known journals, I was asked to participate in the panel comprised of three doctoral students and three faculty members.

120th American Political Science Association (APSA) Annual Meeting & Exhibition

September 7, 2024

Philadelphia, PA

Chair: Betina Cutaia Wilkinson, Wake Forest University

Roundtable on Climate Change and Vulnerable Populations

George Mason University “Brown Bag” Workshop

February 7, 2024

Arlington, VA (remote)

Topic: Paper on “The Effect of Slow-Onset Climate Change on Migration Decisions” by Justin Gest, Lucas Núñez, Scott Drinkall, Kapiolani Micky

Presenters

Lucas Nunez & Scott Drinkall

Follow-up Items

Review literature on knowns/unknowns and the sense of urgency. More generally, the literature on response to uncertainty.

Clarify the role of slow-onset and fast-onset events: how does uncertainty affect the way people think about the migration decision?

Draw in literature from disaster studies regarding slow- and fast-onset.

Explore more why health is so essential—related to the infrastructure of the FSM?

Discuss more heterogeneous effects on the non-climate attributes, e.g., those with health problems are more reactive to health components, people with children are less reactive to the family components (have ties to the land). Explore these further.

Find the proportion of those who had health issues. Interpret the results further regarding health.

Association for Public Policy Analysis & Management (APPAM)

November 18, 2022

Washington, D.C.

Student Research - Impacts of COVID-19 and Medicaid Expansion on Immigrants & Refugees

(Population and Migration Issues)

Chair: Jim P Stimpson, Drexel University

Discussants: Sarah Charnes, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Ngoc Dao, Kean University

“Migration in the Midst of a Pandemic: A Case Study of Pacific Islanders in Oregon”

The APPAM 2022 Fall Research Conference was held in Washington, D.C. at the Washington Hilton. The theme was Advancing Policy Research with Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives.

The 2022 APPAM Fall Research Conference program included pre-conference workshops on November 16, a Presidential Address on November 18, and the main conference sessions from November 17-19 in Washington D.C. The multi-disciplinary conference featured panels, roundtables, and poster presentations on various policy areas, along with special events like wellness sessions, a PhD Fair, and affiliate receptions.

I was a presenting author in the session: Impacts of COVID-19 and Medicaid Expansion on Immigrants & Refugees (Population and Migration Issues) with other student researchers. The session discussants provided extensive feedback on our paper before opening for public Q&A

Angesom Teklu, University of Massachusetts, Boston

Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on African Immigrant and Refugee Population in the City of Boston

Abstract

The Pacific Islander population in the United States continues to grow due to outmigration and a unique immigration arrangement. Under the Compacts of Free Association (COFA), citizens from three Remote Oceania countries can travel to the United States to live and work without restriction. Given the special status of COFA migrants, there is a growing interest among policymakers and researchers to better understand this population, which has often been overlooked. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has recently spotlighted this community due to their exceedingly high rates of infection, hospitalization, and morbidity. This study examines how migration is experienced during a pandemic via a case study of first-generation Micronesians living in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, one of the largest Micronesian communities in the United States. Interviews reveal how social determinants of health – such as economic stability, non-discrimination and equal treatment, access to healthcare, employment, and housing – may contribute to unequal health outcomes between Pacific Islander immigrants and other racial and ethnic populations. These determinants also contribute to human dignity. Using the emergent Migration with Dignity framework, this study assesses how the pandemic has challenged the six dimensions of dignity and disrupted the migration experience, including the push-pull factors for deciding to emigrate to and stay in the United States. Finally, the study assesses resources available for COFA citizens and avenues for improved support.

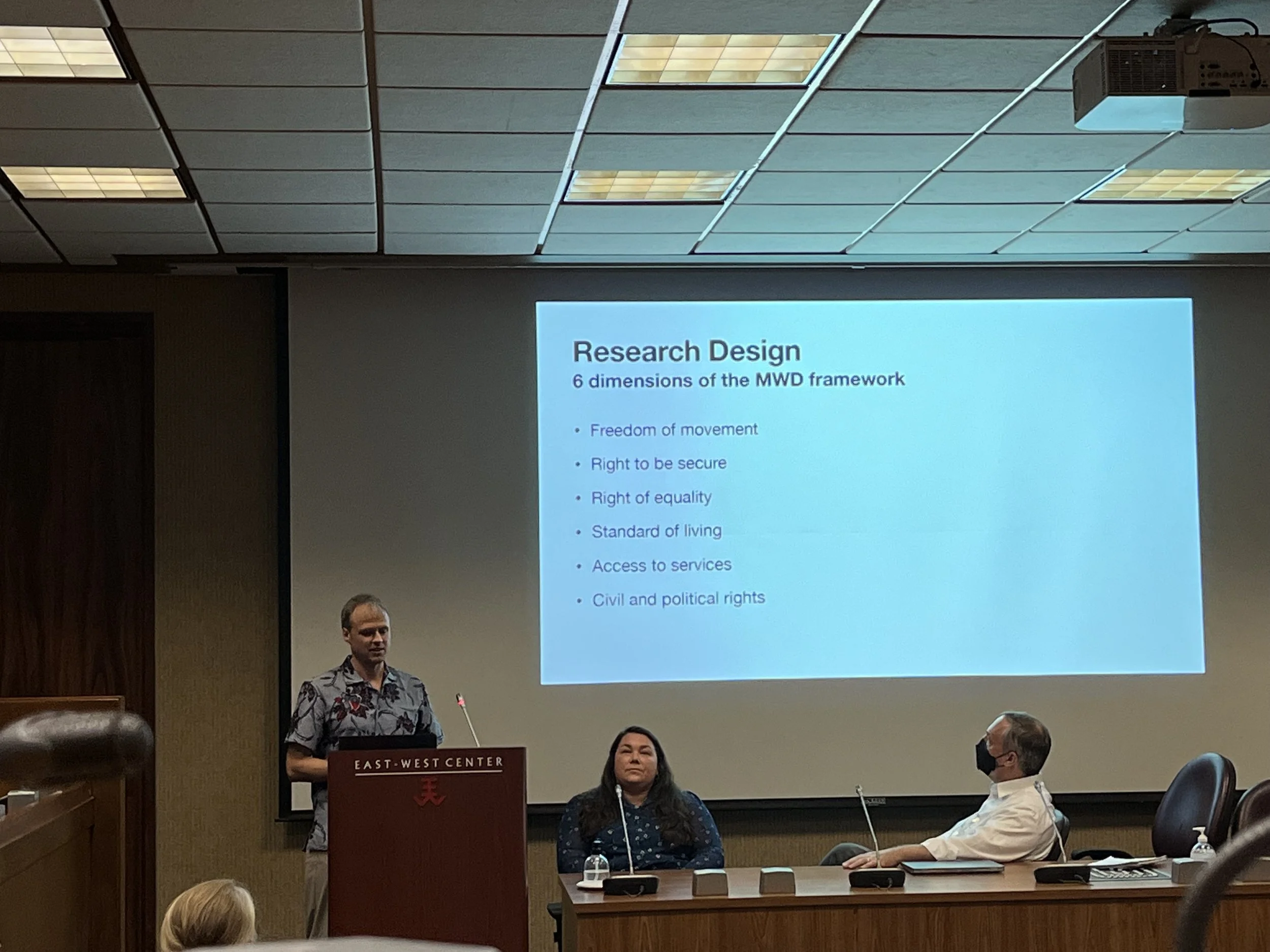

Migration with Dignity From the Pacific Islands Countries: Climate Change, Pandemics, Livelihood, and Infrastructure

September 8, 2022

Honolulu

Presentation: “Migration in the Midst of a Pandemic: A Case Study of Pacific Islanders in Oregon”

In collaboration with the Center for Pacific Islands Studies (CPIS), the Ocean Policy Research Institute (OPRI), the Environmental Law Institute (ELI), the Global Infrastructure Fund Research Foundation Japan, and others, our research team presented on vulnerabilities and agency of Pacific Islander migrants.

Opening remarks: Suzanne Vares-Lum, President, East-West Center; Peter Arnade, Dean, College of Arts, Languages & Letters, University of Hawaiʻi Mānoa; Alexander Mawyer, Director, Center for Pacific Islands Studies

Affiliates: Center for Pacific Islands Studies, University of Hawai’i at Manoa; Ocean Policy Research Institute, Sasakawa Peace Foundation; Global Infrastructure Fund Research Foundation Japan; Hosei University; Environmental Law Institute; Pacific Islands Development Program

Opening remarks

Session 1

George Mason Graduate Interdisciplinary Conference

Arlington, VA

April 8-9, 2021

“Migration in the Midst of a Pandemic: A Case Study of Pacific Islanders in Oregon” (preliminary findings)

The Graduate and Professional Student Association hosted the 2021 Mason Graduate Interdisciplinary Conference. On behalf of our team, I presented our preliminary findings on Phase II of the Migration with Dignity work. The abstract can be read here.

JDR Rollout Seminar, “Climate Change, Migration, and Vulnerability’

Tokyo

January 23, 2020

“Climate Change, Migration, and Vulnerability”

The Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation (OPRI-SPF) invited our team to participate in a roll-out event for the Journal of Disaster Research Special Issue on Climate-Migration and related meetings held in Tokyo, Japan. This opportunity afforded us the chance to meet with other researchers from around the globe, friends at the Ocean Policy Research Institute, and new acquaintances who attended the roll-out.

The authors are grateful to the Ocean Policy Research Institute of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation and the Nippon Foundation for their support of this research.

Environmental Law Institute Panel on Migration with Dignity: Lessons from Pacific Islanders in the United States

Washington, D.C.

March 12, 2019

Migration is increasing from the Pacific Islands to the mainland United States for several factors, including education, jobs, family, and health. Though climate change is not (yet) a primary driver of emigration, it is often cited as a reason to not return to the islands. This migration often happens quite quickly, with little planning, and the transition to a new way of life may not occur as seamlessly as hoped.

In 2014, then-President Anote Tong of Kiribati announced the intention to empower his people to Migrate with Dignity. Though still emerging in conceptualization, this framework seeks to maintain cultural integrity and ensure access to education, employment, and healthcare without losing the skills and knowledge migrants received in their parent country. With these elements in mind, the Environmental Law Institute, the University of Tokyo, Hosei University, the Micronesian Islander Community, and the Arkansas Coalition of the Marshallese have designed and undertaken research studies to understand better the elements that both support and challenge the concept of Migration with Dignity.

Discussed were several lessons learned from Pacific Islanders in the United States, and how the concept of Migration with Dignity can be developed with this shared knowledge.

Presented on the following:

“Migration of Pacific Islanders to Oregon: Assessing Quality of Life Facilitators and Inhibitors”

Migration from Pacific Islands to the mainland United States has been increasing for several factors, including education, jobs, family, and health. Though climate change is not (yet) a primary driver of emigration, it is often cited as a reason not to return to the islands. This migration often happens quite quickly, with little planning, and the transition to a new way of life may not occur as seamlessly as hoped.

In collaboration with the Environmental Law Institute, we shared lessons learned from Pacific Islanders in the United States and how the concept of Migration with Dignity can be built with this shared knowledge.

Panelists:

Carl Bruch, Environmental Law Institute, Moderator

Mikiyasu Nakayama, Professor and Department Head, Environmental Studies, University of Tokyo

Melisa Laelan, Director, Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese

Kapiolani Micky, Certified Health Worker, Micronesian Islander Community

Shanna McClain, Visiting Policy Analyst, Environmental Law Institute

Scott Drinkall, Visiting Researcher, Environmental Law Institute

Cosponsored by: Environmental Law Institute, University of Tokyo, Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese, Micronesian Islander Community, and Hosei University

Community Forum

Oregon

March 9, 2019

“A Portrait of Migration: Experiences of First-Generation Chuukese, Marshallese, and Palauans in Oregon”

In both Portland and Salem, we shared results of research studies that seek to better understand the motivations and experiences of Micronesians who emigrate and establish new lives abroad. Special attention was given to research results of first-generation Chuukese, Marshallese, and Palauans who have emigrated to Oregon. Community members, including some of those we interviewed, discussed the study results, implications, and facilitators and barriers for improved lives.

Chemeketa Community College (Salem)

Rosewood Initiative (Portland)

International Seminar & Experts Meeting, East-West Center

Honolulu

February 18-19, 2019

“Migration with Dignity: A Case Study on the Livelihood Transition of Micronesians to Portland and Salem, Oregon”

In this international seminar, “Aspirations and Livelihood Transition of Migrants from the Pacific to Abroad” at the Imin International Conference Center, East-West Center, we discussed findings from surveys on the issue of so-called Climate Refugees from SIDS. Emphasis was placed on (a) education and training before migration and (b) livelihood re-establishment after migration.

Following the seminar was an experts meeting on “How Religion, Culture and Education Influence the Perception of People about Climate Change.” The events were organized by the Department of International Studies, The University of Tokyo; the Environmental Law Institute; Faculty of Sustainability Studies, Hosei University; and the Ocean Policy Research Institute.

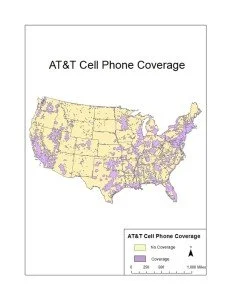

Association of American Geographers

Los Angeles

April 2013

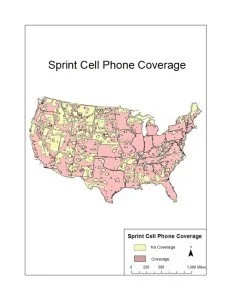

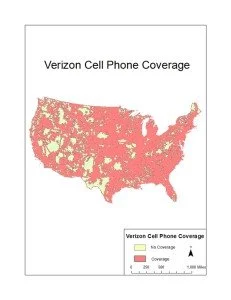

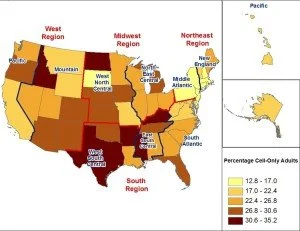

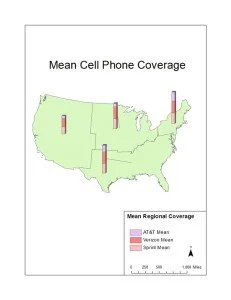

“Geographic Variations in the Cell Phone-Only Population”

(Co-authored)

Data analysis uses critical thinking skills to look at trends and come to conclusions based on findings. It also requires attention to detail and vigilance in computations. Essentially, it is about translating numbers into plain English and making informed decisions based on that knowledge, which is valuable for market research or logistics.

Findings from a statistical analysis of cell phone-only households were presented at the 2013 American Association of Geographers Conference in Los Angeles by Professor Ira Sheskin at the University of Miami.

AT&T

Sprint

Verizon

A state-level analysis

Regional coverage for three major providers

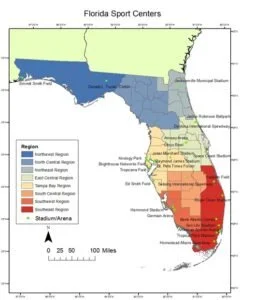

Florida Society of Geographers

Gainesville

February 2011

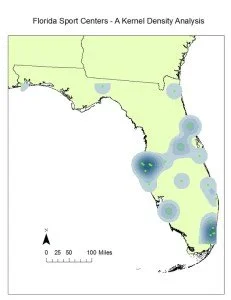

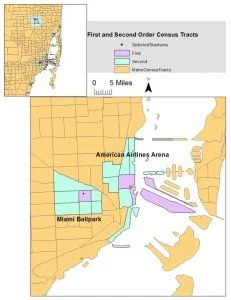

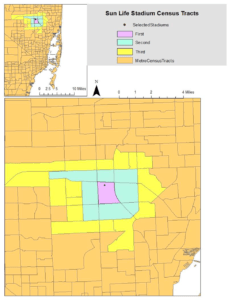

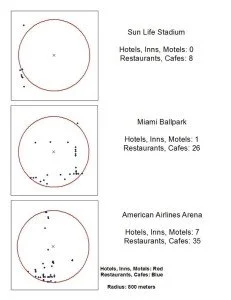

“An Analysis of the Socio-Economic and Demographic Effects of Miami-Dade’s SunLife Stadium”

As a member of the Florida Society of Geographers, I presented my work on the promotion of stadiums and their socio-economic and demographic effects at various scales at the annual conference.

Spatial-statistical analysis and ArcGIS were incorporated to address concerns over developers’ and politicians’ promises of neighborhood revitalization, assessing socio-economic effects spatially and temporally, and how prevailing ideas in the sport tourism literature are both affirmed and challenged by stadium development.

Chair: Dr. Mary Caravelis

To conduct the investigation, the following questions are asked:

1) Where is the sports arena located?

2) What are the socio-economic effects of the stadium on the surrounding neighborhood over time?

To assess changes following the building of the stadium (now called Hard Rock Stadium), I analyzed Census tracts at different time periods and distances. Drastic changes occurred in the years before and after the stadium was built, even when compared to the region. For instance, the white population decreased by 92% while housing prices nearest to the stadium increased more than those farther away.

Comparisons were made with other sports venues in the area. Footprints with a 800 meter radius show the associated businesses.

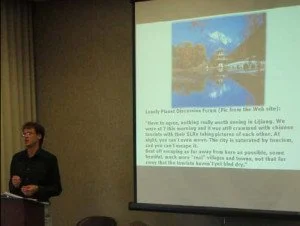

International Graduate Student Conference, University of Hawai’i

Honolulu

February 11-13, 2010

“Tourism Geography in Lijiang, China: Touristification and Socio-Spatial Transformation of a World Heritage Site”

Moderator: Ricardo D. Trimillos, Professor and Chair of Asian Studies

“Graduate student Scott Drinkall presented

‘Tourism Geography in Lijiang, China:

Touristification and Socio-Spatial

Transformation of a World Heritage Site’ at

The 9th Annual International Graduate

Student Conference at the University of

Hawaii, Manoa. Scott analyzed how spatial

connections through tourist consumption of

shopping, photography, music, and dance have

molded Lijiang’s heritage landscapes into

iconic images that now serve as reference

points for potential consumers.”-University of Miami Geo-jottings and Perspectives, 2010

Literary Magazine Editor

Book Editing

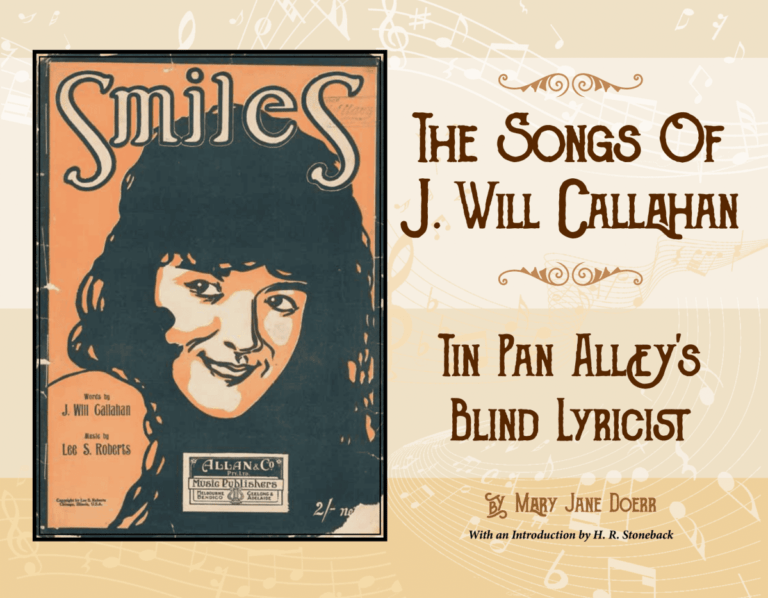

Smiles: The Songs of J. Will Callahan

Tin Pan Alley’s Blind Lyricist

Catch a glimpse into a bygone era of songs set against the 1918 flu epidemic, racial relations, social ills, and much more. Award-winning author and historian Mary Jane Doerr, along with H.R. Stoneback, an internationally renowned scholar with expertise in the life and work of Hemingway, uncover the Northern Michigan connections to one of the most influential songwriters in American history.

Apple Podcast: Tales of Northern Michigan’s Past

2023 New York Book Festival, General Non-Fiction Honorable Mention